Campephilus principalis

SUBFAMILY

Picinae

TAXONOMY

Picus principalis Linnaeus, 1758, based on Mark Catesby’s drawing

of the “Largest White-bill Woodpecker” from South Carolina.

Two subspecies recognized.

OTHER COMMON NAMES

French: Pic а bec ivoire; German: Elfelbeinspecht; Spanish:

Carpintero Real.

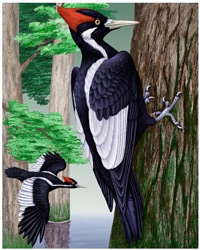

PHYSICAL CHARACTERISTICS

18.5–21 in (47–54 cm); 15.5–18.3 oz (440–570 g). A very large,

black woodpecker with white lines extending down the neck on

each side to the upper base of the wing, white secondaries and

inner primaries, a very robust, chisel-tipped, ivory-colored bill;

male has a pointed crest that is black in front and scarlet behind;

female has a longer, more pointed, somewhat recurved

solid black crest.

DISTRIBUTION

C. p. principalis formerly found in southeastern United States

from eastern Texas to North Carolina and north to southern

Illinois and southern Ohio; C. p. bairdi formerly in forested

areas throughout Cuba. Most recent known populations are

from northeastern Louisiana, Florida, and northeastern Cuba.

May now be extinct, though continued unverified reports in

southeastern Cuba, southeastern Louisiana, and Florida provide

hope.

HABITAT

Extensive old-growth forest, especially bottomland forest, but

also pine uplands in both the United States and Cuba; habitat

losses resulted in last North American populations being in

bottomlands and last Cuban populations being in upland

pines.

BEHAVIOR

Wanders over a home range of 6 sq mi (15.5 sq km) or more;

perhaps somewhat social, often seen in family groups; characteristic

call is a plaintive, single- or double-note nasal tooting

that has been likened to a child’s “tin horn” and that can be

mimicked by blowing on a clarinet mouthpiece; mechanical

sound produced is a hard single pound on a resonant surface

followed immediately by another such that the second sounds

like an echo of the first. This mechanical sound is characteristic

of Campephilus woodpeckers and is called the “double

rap.”

FEEDING ECOLOGY AND DIET

Visits recently dead trees and with its heavy, chisel-like bill,

knocks large slabs of bark from the tree to reveal subsurface

arthropods. Feeds extensively on the larvae of large wood-boring

beetles, especially Cerambycidae; also takes other arthropods

and fruit in season.

REPRODUCTIVE BIOLOGY

Monogamous; known to breed from January through April in

North America and March through June in Cuba, but few data

are available. Nest cavity is in a large dead tree or in a live tree

with extensive heartrot. Recorded nests have been 24–50 ft

(7.3–15.2 m) up; cavity entrance typically taller than wide, but

shape varies. Clutch 2–4 eggs; incubation by both parents; incubation

period and age at fledging not known; young may remain

with parents until next breeding season.

CONSERVATION STATUS

Critically Endangered by all criteria; may be extinct. The major

factor leading to current status has been loss and fragmentation

of old-growth forest, but other factors have been

nineteenth century killing of birds by scientists, amateur collectors,

Native Americans, and hunters, and probably more recent

limitation of natural fire. In North America, confusion

with the similar-sized and similar-appearing pileated woodpecker

(Dryocopus pileatus) leads to many false sightings.

SIGNIFICANCE TO HUMANS

Bills and scalps of males were culturally important to Native

Americans, apparently symbolic of successful warfare. They

were often used to decorate war pipes and medicine bundles

and were widely traded outside the range of the species. Early

Europeans in North America also killed the birds for their

bills and used them for such things as watch fobs. In the late

1800s, there was a brisk trade in skins and eggs among private

and professional collectors. In both the United States and

Cuba, ivory-bills were occasionally eaten. The ivory-bill has

become symbolic of rarity. Collector prints, ceramic ivorybills,

trade cards with ivory-bills on them, and use of ivorybills

in advertisements have drawn much attention to the

species.

Photo Gallery of - Ivory-billed woodpecker

Animalia Life

Animalia Life