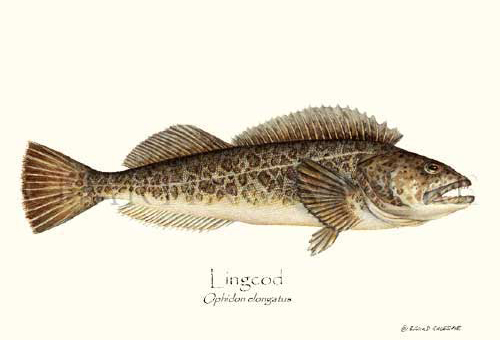

Ophiodon elongatus

FAMILY

Hexagrammidae

TAXONOMY

Ophiodon elongatus Girard, 1854, San Francisco, California,

United States. Sometimes placed in

FAMILY

Ophiodontidae.

OTHER COMMON NAMES

English: Cultus cod, ling.

PHYSICAL CHARACTERISTICS

Lingcod are large, up to 5 ft (1.5 m) in length and 100 lb (45

kg) weight (males smaller), and have a large mouth extending

behind the eyes. The mouth has prominent teeth. The spiny

and soft dorsal fins are joined to form one long, moderately

notched dorsal fin running the entire length of the body behind

the head, and the tail fin is squared, not forked. The

color is brown, rarely blue-green, with a staggered array of

black blotches along the body midline and top.

DISTRIBUTION

From Ensenada, Mexico (Baja California), to the Alaska Peninsula

(Shumigan Islands).

HABITAT

Lingcod spawn on rocky reefs along the shoreline, usually at

depths of about 33–99 ft (10–30 m), but spawning has been observed

in the intertidal and by submarine at much greater

depths. The females migrate onto sand and mud bottoms at

greater depths up to 330 ft or more (100 m), except when they

return inshore for spawning, whereas males tend to remain all

year on the spawning reefs. Lingcod will hide in crevices.

Young lingcod tend to be more generally distributed near the

shoreline, avoiding areas occupied by adults. Recently settled

lingcod have been collected in eelgrass beds and have been

seen from a submarine on flat bottom at the base of a cliff over

360 ft (110 m) deep.

BEHAVIOR

Aside from male territoriality, female seasonal migrations, and

rapacious predatory

BEHAVIOR

, lingcod tend to be sedentary

ambush predators. They rest near rocks and wait for prey to

swim near. During salmon migrations, however, lingcod have

been observed predating at the surface over great depths, so

relative abundance and position of prey affect

BEHAVIOR

.

The life history of lingcod relates closely to that of Pacific

herring. Larval lingcod settle from the plankton at the time

during spring when herring larvae are becoming silver juveniles.

Young lingcod that have not settled permanently from a swimming

habit search in school formation during the twilight hours

of dawn and dusk, and young herring are their favorite prey.

FEEDING ECOLOGY AND DIET

Although lingcod will eat invertebrates such as crabs,

shrimps, and octopi, they mainly feed on other fishes, including

younger lingcod. A lingcod engulfs another fish headfirst.

The throat rapidly opens while the mouth engulfs the

prey, so that a fish about two-thirds the length of the lingcod

will be swallowed immediately into the entire length of the

stomach, with only the tail protruding from the mouth. During

years of abundant prey, growth is rapid. After two years

lingcod of both sexes tend to reach about 1.5 ft (46 cm) in

length, after which males grow more slowly than females,

perhaps owing to the seasonal feeding migration that only females

undertake.

REPRODUCTIVE BIOLOGY

Males become jet black and fight over territory during winter,

prior to arrival of ripening females. Males will successively

spawn with different females, guarding up to three egg

masses at a time. Males are capable of spawning at two years

of age, and females at three, but most females do not lay eggs

until they are four. If larger females are not abundant, then

females tend to mature and spawn a very small egg mass at

three years of age. In British Columbia, peak abundance of

guarded egg masses is during February, although spawning

can occur from December through April. Spawning occurs

later in more northerly latitudes. Older females of 10–15

years of age can spawn a half million eggs, and they spawn

earlier and deeper than the younger fish. Larvae spawned by

the largest females tend to be slightly larger than larvae of

small females, which could confer advantage under certain

feeding conditions in the plankton. Thus, a population with a

full demographic spread from young to old fish will have

greater chances of survival of young under a variety of environmental

conditions.

CONSERVATION STATUS

Not listed by the IUCN. Lingcod have been extremely depleted

since the 1980s in Puget Sound, and since the 1990s in the

Strait of Georgia. Outer coast populations have become overfished

in more recent years. It has been demonstrated mathematically

that even the earliest hand-line fisheries prior to

World War II led to significant reduction in lingcod biomass in

inland seas around Vancouver and Seattle. More efficient otter

trawls in the 1940s greatly increased levels of landings, which in

British Columbia exceeded eight million pounds per year (over

3,700 metric tons). Landings in the Strait of Georgia were negligible

when the commercial fishery closed in 1990, but since

then it has become evident that sport fishing alone can prevent

population recovery near metropolitan areas. Lingcod are of interest

for management strategies that include protection within

sanctuaries (marine protected areas).

SIGNIFICANCE TO HUMANS

The common name “cultus” is a Coast Salish term meaning

“cheap,” which indicates that original levels of abundance ensured

that lingcod could be caught for use as food when preferred

species like halibut became less available. As

mentioned, lingcod has always been valued as a fresh fish.

Aquaculture is possible but not yet economical. Appreciation

of the value of lingcod as a sport species tends to increase as

the availability of this and other groundfish species declines

in a given area.

Other popular Animals

Photo Gallery of - Lingcod

Animalia Life

Animalia Life