Pterosaurs ("winged reptiles") were flying reptiles

of the Mesozoic Era, and the first of only

three vertebrate groups known to have evolved

active flight. Pterosaurs first appear in the paleontological

record about 225 million years ago,

during the late Triassic Period, and persist to the

terminal Cretaceous extinction event, about 65

million years ago.Pterosaurs are recognized as being

members of the group Archosauria, a group

including thecodonts, crocodiles, birds, and dinosaurs.

While pterosaurs were contemporaries to

the great Mesozoic dinosaurs, and often confused

with them, pterosaurs were not dinosaurs.

The origin of pterosaurs is a subject of great debate.

Pterosaurs share some physical characteristics

in the hips and legs with early dinosaurs. It

has also been suggested they could run bipedally

and took to the air by the energy-consuming

method of running and flapping their wings. Another

view suggests pterosaurs pursued a treedwelling

way of life, and developed parachuting,

gliding, and eventually flight as an energy-saving

byproduct of their lifestyle. Another debate surrounds

whether pterosaurs were warm-blooded

or cold-blooded creatures. Some fossil remains

suggest certain pterosaurs may have been covered

with short, thin fur, or even very fine feathers.

This, combined with the energy-consuming

activity of flying, leads many researchers to favor

warm-blooded pterosaurs.

The first pterosaur fossils were discovered in

the Solnhofen Limestone Formation in Germany,

in 1784. Pterosaur fossils range in size from those

of Pterodactylus, whose forty-centimeter wingspan

was about that of a modern song bird, to

Quetzalcoatlus, whose fifteen-meter wingspan was

as big as a modern private aircraft wing. Pterosaurs

had light, bony skeletons made of hollow, tubular

bones, and compact bodies to improve wing support.

The pelvis and hind limbs were small, yet

long and slender when compared to the fore limbs

and shoulders. The fore limbs were exaggerated

in comparison to the hind limbs, with their great

length derived from the extended fourth finger,

which alone supported the flight patagium. The

pterosaur patagium was a soft membrane thought

to have been tougher and thicker than a bat's

wing, and divided into three anatomical segments.

One short segment stretched from the torso to the

elbow end of the humerus; a second, longer segment

stretched from the radius and ulna and the

bones of the wrist and palm; and the third, longest

segment was an elongated fourth finger supporting

the wing membrane to its tip. The segments of

the wing were progressively longer as they got

farther from the trunk. The first, second, and third

fingers were not involved in membrane support

but were free to grasp and cling; there was no fifth

finger. This "finger-wing" configuration is quite

different from the wing support structure seen in

bats and birds.

Types of Pterosaurs

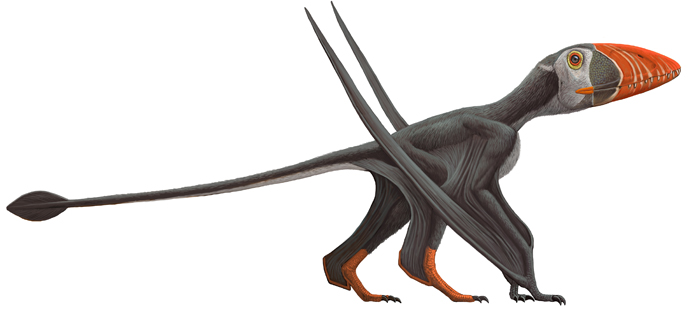

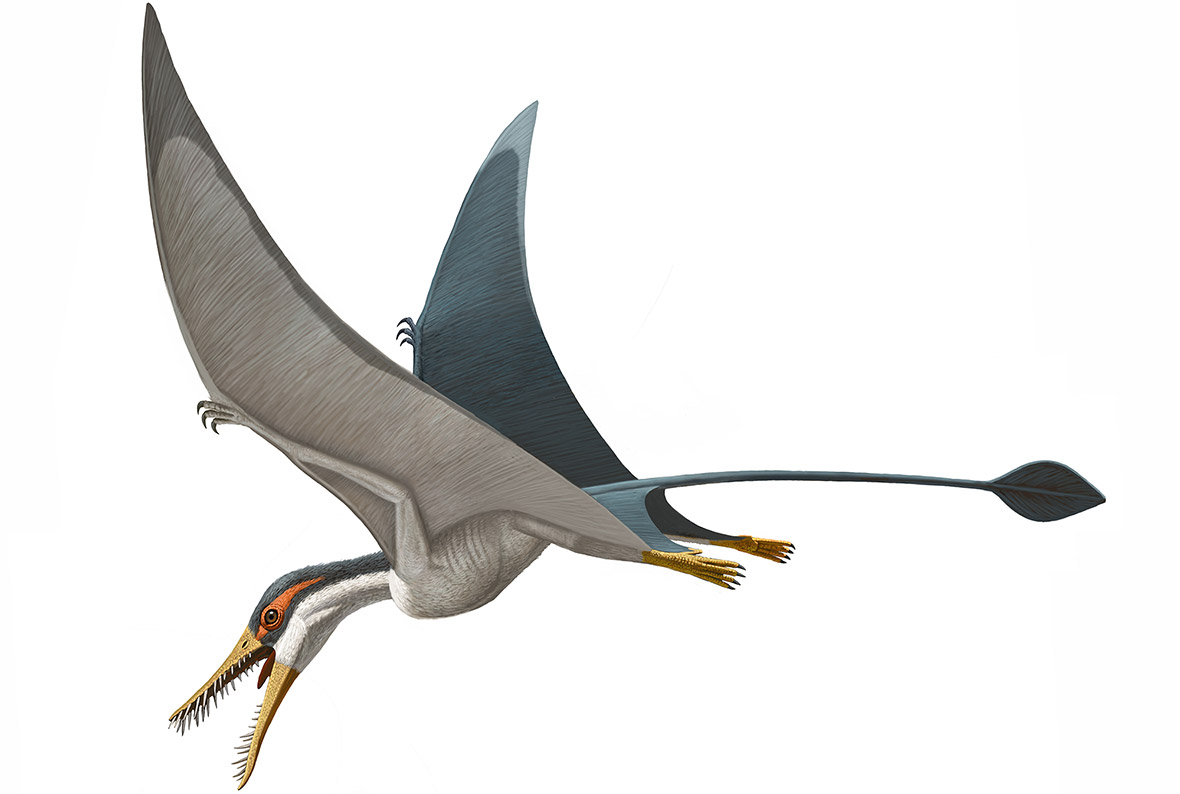

Pterosaurs are generally divided into two groups:

The rhamphorhynchoids first appear during the

Triassic, and the pterodactyloids appear some 108

million years later. The Rhamphorhynchoidea

had teeth, long tails, short metacarpals, long fifth

toes, and a head held in front of and slightly above

the torso. The Pterodactyloidea had no tail or fifth

toe, an elongated metacarpus forming the largest

support structure of its wing, a more "birdlike"

neck posture with the neck curving in an S-shape

entering the cranium frombelow rather than from

behind, holding the head higher above the torso,

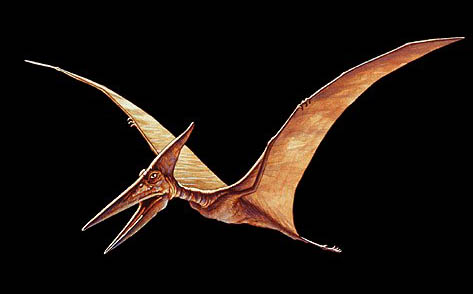

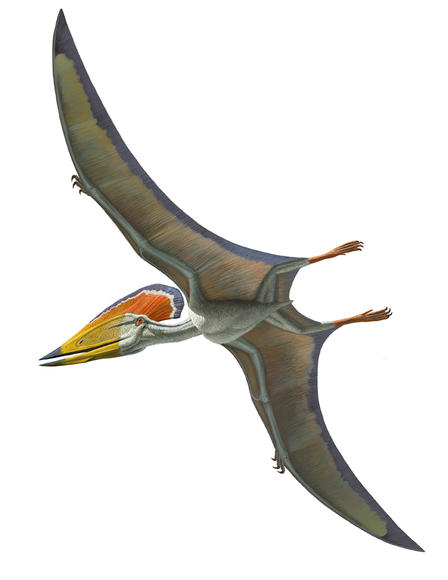

and many had evolved toothless beaks. Pterodactyloidea,

such as Pteranodon, also evolved extreme

head crests, and like many later pterosaurs,

lacked well- developed teeth. Many other pterosaur

fossils exhibit well-developed and specialized

teeth: Eudimorphodon and Dorygnathus had

teeth designed to spear and hold prey; Dsungaripterus

had bony jaws and broad, flattened teeth to

winkle out shellfish and snails; and Pterodaustro

had a comblike array of teeth, ideal for sieving

plankton.

The majority of pterosaur bones have been recovered

from marine sedimentary rock deposits,

suggesting these flying reptiles took advantage of

the atmospheric updraft conditions of gentle and

constant breezes along shorelines, as well as the

abundant food of the marine environment.

Pterosaur aerodynamics and flight characteristics

have been studied in great detail, and they suggest

pterosaurs were active, wing-flapping fliers,

but also better gliders than are most modern bird

species. Pterosaur anatomy suggests they were

able to glide and soar over great distances and for

extended periods of time under calm conditions,

but that they were not well adapted for staying

aloft under turbulent conditions. It is estimated

that the pterosaur Pteranodon, who represents one

of the high points in pterosaur evolution with a

wingspan of over seven meters, could soar at

speeds in excess of 30 kilometers per hour, continue

gliding aloft for nearly twenty hours, and possibly

cover distances of over 750 kilometers without

landing.

The greatest number of pterosaur bones have

been recovered from the Kansas marine chalk deposits

of North America. Over eight hundred

skeletal fragments have been found there. While

many of the remains suggest these Kansas

pterosaurs died nonviolently, other bones suggest

the pterosaurs were eaten by marine reptiles. Apparently,

pterosaurs swooping low to snatch prey

fromthe ocean's surface were often in turn preyed

upon by larger marine reptiles or sharks.

Pterosaur Facts

Principal Termsarchosaurs: diapsid reptiles whose skeletal evolution distinguishes them from the diapsid lepidosaurs

Mesozoic Era: the middle era of the Phanerozoic eon, 250 million to 65 million years ago

patagium: a soft, flexible membrane

Other popular Animals

Photo Gallery of - Pterosaur

Animalia Life

Animalia Life