Pseudopleuronectes americanus

FAMILY

Pleuronectidae

TAXONOMY

Pleuronectes americanus Walbaum, 1792, New York.

Solea solea

Pleuronectes platessa

OTHER COMMON NAMES

English: Blackback, Georges Bank flounder, lemon sole, rough

flounder; French: Limande-plie rouge; Spanish: Solla roja.

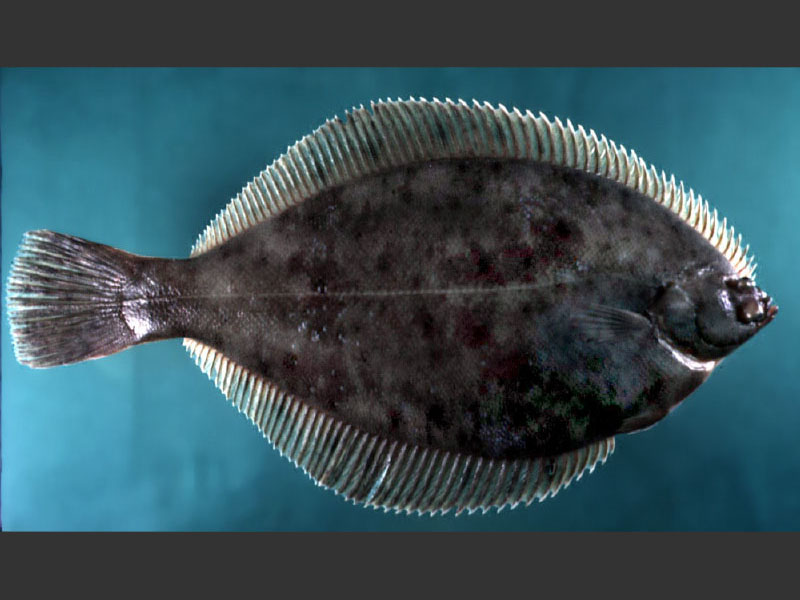

PHYSICAL CHARACTERISTICS

Medium-sized, dextral flatfish with an oval and thick body with

a relatively wide caudal peduncle and a broadly rounded caudal

fin. The head is relatively small, with a small terminal mouth

with a small gape and thick, fleshy lips. Jaws on the blind side

are equipped with a series of incisor-like teeth, whereas the jaws

on the ocular side are toothless or nearly so. The lateral line is

nearly straight, with only a slight arch above the pectoral fin.

Ocular side scales are ctenoid, whereas blind side scales are

ctenoid in males and cycloid in juveniles and females. Winter

flounder vary in color, depending on the bottom where they

live. Larger specimens are dark muddy brown or reddish brown,

olive-green, or slate-colored to almost black. On the ocular side,

coloration varies from uniformly pigmented to patterned with

definite flecks, spots, and darker blotches of differing hues, depending

on the bottom type. The blind side usually is uniformly

white and translucent with a bluish tinge toward the body margins

and sometimes with yellow on the caudal peduncle. Winter

flounder can attain a length of 24.8–26.4 in (63–67 cm) and

weights to about 7.9 lb (3.6 kg). Winter flounder are relatively

long lived, reaching a maximum age of about 15 years. After

about age five, females begin to grow faster than males; they

also live longer than males.

DISTRIBUTION

Western North Atlantic in estuarine and marine waters along

the Atlantic coast of North America from Labrador south to

Georgia and also on the offshore banks. Most abundant between

the Gulf of Saint Lawrence and Chesapeake Bay.

HABITAT

Brackish waters of tidal rivers, estuaries, and river mouths to

areas on the inner continental shelf. Larger and older fish tend

to inhabit deeper waters than do younger, smaller fish. Typical

inshore habitats consist of muddy sand, especially where the

sand is broken by patches of eelgrass; clean sand; clay; and

pebbly and gravelly ground. Offshore, winter flounder usually

are found on hard bottom. They can survive a wide range of

temperatures, from nearly the freezing point of saltwater to

about 68–69.8°F (20–21°C). Their blood serum contains an

antifreeze protein that helps protect them against freezing.

BEHAVIOR

Diurnally active, with activity beginning at sunrise. At night

they lie flat, with heads resting on the bottom and eye turrets

retracted. On muddy bottoms, winter flounder usually lie

buried, all but the eyes, working themselves down into the

mud soon after settling on the bottom. Fish living on tidal flats

typically remain motionless during low tides but actively forage

during high tides. Can change color to match background surroundings,

ranging from whitish on white backgrounds to dark

brown or nearly black on dark sediments. Local conditions in

inshore waters appear to determine inshore

DISTRIBUTION

patterns,

whereas offshore movements seem to be associated with

extreme summer and winter conditions. In general, in summer

months adult winter flounder stay in the shallow shore zone

when the water temperature is not excessive and food availability

is adequate. If these conditions are not met, they may move

into deeper channels or offshore or may take evasive action.

During winter in the southern parts of their range, they remain

or move into shallow water to spawn, whereas in northern

regions they remain inshore in protected areas and move

offshore in exposed areas to avoid turbulence and drifting pack

ice. Winter flounder in deeper waters, such as Georges Bank,

remain there year-round. Winter flounder bury in sediments

when water temperatures are below 32°F (0°C) and ice crystals

are present in the water. They are active at water temperatures

up to 71.6°F (22°C), beyond which they become inactive. They

are sensitive to low levels (3 ppm) of dissolved oxygen.

FEEDING ECOLOGY AND DIET

Visual predators. Consume a wide variety of small invertebrates

and, rarely, small fishes, such as sand lance. Principal

food includes polychaetes, anthozoans, and amphipods but also

shrimps, small crabs and other crustaceans, ascidians,

holothurians, squids, bivalve and gastropod mollusks, and

sometimes fish eggs. They often bite off clam siphons that

protrude from the sand. While feeding, a winter flounder lies

with its head raised off the bottom with its anterior body

braced vertically against the bottom. Eye turrets are extended,

and the eyes move independently of each other. After sighting

its prey, the fish remains stationary, pointed toward the target,

and then lunges forward and downward to seize its prey. Winter

flounder are eaten by codfish, spiny dogfish, goosefish,

hakes, winter skate, smooth dogfish, striped bass, bluefish, sea

raven, seals, ospreys, gulls, blue herons, and cormorants.

REPRODUCTIVE BIOLOGY

In the fall, as gonads ripen, adult winter flounder remain in or

move into shallow water to spawn. They spawn in winter in

southern locations and in early spring (January to May) in

more northern locations. Spawning in inshore waters occurs

nearly at the seasonal lowest temperatures, which range from

31.1 to 35.6°F (_0.5–2.0°C), depending on latitude. Spawning

on Georges Bank happens at temperatures ranging from about

37.9 to 41.9°F (3.3–5.5°C). Winter flounder spawn on sandy

bottom and algal mats, often in shallow water. Spawning in estuaries

occurs in areas with salinity levels as low as 11.4 ppt.

Males mature at age two and females at age three off New

York, when fish are 7.9–9.8 in (20–25 cm) in total length. Fish

in more northern areas mature later—age three years and four

months for males and three years and six months for females

north of Cape Cod and age six for males and seven for females

in Newfoundland. Maturity seems to be a function of size

rather than age. On Georges Bank, the mean age at maturity is

just under two years for both sexes.

Females produce, on average, 500,000 eggs, but larger fish

can produce up to 3.5 million eggs. Winter flounder migrate

into shallow water or estuaries and coastal ponds to spawn, and

tagging studies show that most return repeatedly to the same

spawning grounds. They are batch spawners. Females in captivity

spawned up to 40 times and males up to 147 times.

Males initiated all observed spawning events, which occurred

throughout the night but primarily between sunset and midnight.

Spawning by one pair frequently elicited sudden convergence

and spawning by secondary males. Strict pair spawning is

uncommon. Male and female activity patterns were almost entirely

nocturnal during the reproductive season but became increasingly

diurnal during the post-spawning season. Eggs are

fertilized outside the body and sink to the bottom, where they

stick together in clusters. Incubation takes place over 15–18

days at 37–37.9°F (2.8–3.3°C). Young larvae hatch at about

0.12–0.14 in (3.0–3.5 mm). Metamorphosis is complete when

larvae are only 0.31–0.35 in (8–9 mm) long. Winter flounder

exhibit little movement from areas where they settle, unless

seasonal temperatures become extreme.

CONSERVATION STATUS

Not threatened, although their numbers have diminished substantially

since the 1970s, and the stocks throughout most, if

not all, of the species’ range are considered to be overexploited.

Overfishing, pollution, and habitats destruction all contribute

to reductions in stock sizes of this species. Current

fishery management plans are to restore stock sizes to former

levels. As of 2002 little success was evident in these attempts.

SIGNIFICANCE TO HUMANS

Highly desirable commercial and recreational species. Winter

flounder were the most frequently captured flatfish taken by

recreational fishers along the eastern coast of the United States

until about 1970. Since then, landings of fish in both commercial

and recreational fisheries have declined substantially.

Other popular Animals

Photo Gallery of - Winter flounder

Animalia Life

Animalia Life